A non-government organization (NGO) is a non-profit, charity-based organization established by individuals to work with charity and philanthropic aids locally and internationally. It is a type of civil society organization offering charity and humanitarian services to citizens. Commercialization in the non-governmental organization has generated a lot of debate in the society. The debate is focused on whether or not NGOs should produce goods and services with the intent of making profit. Those in favour hold on to self-sufficiency as a reason for NGOs commercial services while those against it claim that it opposes the mission of a non-profit organization.

(This article is based on a report originally prepared by Innovation Matters)

Commercialization isn’t really a new phenomenon among NGOs. Scholars like Young et.al (2002) in Bosscher (2009) have argued that NGOs have been establishing commercial ventures since the sector itself began. The only difference now is its scope. Some NGOs offer services like short course vocational training, soft skill training, agricultural related services and training, handicraft shops etc. A good example of this is the running of paid travel tour by religious organizations.

Enlarge

Lagos State Civil Society Partnership and InnovationMatters

Data released by Lagos State Civil Society Partnership (LACSOP) revealed that the largest chunk (61.1%) of NGO surveyed in Lagos embark on capacity-building projects to generate income to sustain their organizations. Education and health projects follow with 59.7% and 52.5% respectively. The LACSOP survey suggests that NGOs are availing themselves of training opportunities directed at capacity-building for their organisations, after which they ‘sell’ the knowledge and expertise acquired over the years.

So, why do NGOs commercialize their services and still assume a non-profit status?

Changing Financial Environment Fuels NGOs Commercialization

NGOs’ commercialization could be triggered by factors such as growing competition, fiscal squeeze and growing country’s population which ultimately increases demand. LACSOP data reveals that fiscal squeeze is a major factor responsible for the commercialization of NGOs’ services.

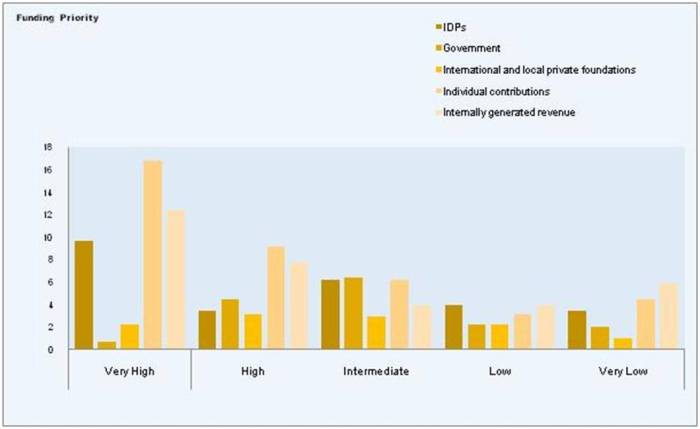

Typically, civil service organizations get funds from different sources such as private sector, international funding sources, rich individuals, national government (which may come in form of tax exemption), private corporation fees and self-generating income. Self-generating income could be in form of membership subscriptions, fees and charges for services (that is, economic activities) and income from investments. Although the last two sources weren’t prominent in the past; things have changed now. LACSOP captures the change in its data below.

Enlarge

Lagos State Civil Society Partnership and InnovationMatters

The highest priority funding rating emerged from individual contributions (16.8%), internally generated revenue (12.4%) and International Development Partners (9.7%). According to LACSOP, this indication gives credence to funding dependence on members’ contributions and the rising trend in internally generated revenue among CSOs. The highlight of the data is the shift from donor dependency to individual contribution and internally generated revenue. NGOs seem to have withdrawn from donor dependency which comes with challenges such as accessing donors, donors’ priorities dictation, donors’ term and conditions for fund eligibility. So, it can be assumed from the data above that the shrink in international donor funding led NGOs to begin to look inward for creative ways of getting funds for survival. One of such ways is the commercialization of their services as revealed in NGOs domain presence chart above.

Enlarge

Lagos State Civil Society Partnership and InnovationMatters

The above data shows another interesting twist to NGOs’ funding challenge. 59% (237) of the respondents attested to the fact that the NGOs they work with operate without formal registration. Only 160 (37%)of the respondents work for NGOs duly registered with Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC), the body responsible for regulating the formation and management of companies in Nigeria. 5 respondents work for NGOs registered outside CAC’s radar. This means that many NGOs operate below the radar in Lagos State. The non-registration status, however, does not imply dormancy in operation.

How then do these NGOs with non-registered status access funds? They couldn’t have been eligible for donors’ funds with such status. The only way out would be the adoption of a self-funding strategy. They must have devised a means of generating funds internally. So, commercialization of services is not far from such NGOs.

The Two Sides of NGOs’ Commercialization

Does the paradigm shift to commercialization have any impact for NGOs? Of course, it does. Opportunities and treats accompany such shift. Guanci Zhang (2014) discussed the benefits of commercializing NGOs services in his paper. He explained that commercialization provides NGOs the opportunity to get rid of the financial control from donors, become self-reliant, and achieve management discipline. NGOs commercial activities will also provide jobs to both volunteers and job-seekers. On the flip side, commercialization may lead to loss of mission and purpose. Mission and money balance may be unachievable; thus, the poor suffers.

Michael Edwards, 2009 further captured the risk. His paper expressed clearly that “a society that reduces everything to a market inevitably divides those who can buy from those who cannot, undermining any sense of collective responsibility and with it, democracy.”

Commercialization will present a new challenge of learning and practicing marketing principles before it can thrive in a competitive market place. In the absence of donor funding, NGOs will need to adapt to marketing skills for survival.