It’s been 59 years since Nigeria joined the World Oil Producers and reaped riches from its oil production. It made its first oil discovery at Oloibiri, Bayelsa in 1956. In 1958, its first oil field came on stream, producing 5,100 barrels per day. By the late sixties and early seventies, Nigeria had attained a production level of over 2 million barrels of crude oil a day. In 2016, the country could boast of 37 billion barrels oil and gas reserve as reported by the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), the State’s oil company. Today, Nigeria’s crude oil production is at 2.2 million barrels per day.

Since 1956, a good number of oil and gas companies (foreign and local) have set up shop in Nigeria. Shell Petroleum Development Company (formerly known as Shell BP) was the first oil and gas company in the country. It drilled 12,008 feet at Olobirin Well No.1 (now dried up). Today, Chevron Nigeria Ltd, ExxonMobil, Nigeria Total, Nigerian Agip Oil Company are some of the other key players in the Nigerian oil market.

What we got from oil and gas in 15 years

Data from the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) shows that companies in the oil and gas sector in Nigeria paid about $347 trillion revenue from 1999 to 2014. This amount was paid to government agencies through a variety of revenue streams such as extraordinary taxes on income, profits, and capital gains, royalties, bonuses, emission and pollution taxes, and general tax on goods and services etc.

While extraordinary taxes on income, profits, and capital gains are paid for the sale of assets like land and properties, general taxes on goods and services are indirect taxes paid on consumption of goods and services by private individuals. Royalties, on the other hand, are paid for the exploitation of natural resources connected with land and minerals. In the oil and gas industry, royalties are pay for oil produced from a concession. he rates are set based on the location of the field. Therefore, the deeper the concession area is, the lower the applicable rate.

Bonuses in the oil and gas industry are paid at a specific time within a project timeline. A very important one is the signature bonus. A signature bonus is paid by a concessionaire at the time an oil prospecting licence or oil mining lease is granted. Finally, emission and pollution taxes are paid for the emission of toxic particles that are devastating to our environment and harmful to health. Oil and gas companies pay a certain amount for gas flared and oil spilled.

In this article, because of their direct impact on host communities and the environment, we focus on the latter: emission and pollution taxes.

Enlarge

OPEN DATA RESEARCH CENTRE, SMC

The charts above help to identify the sources of gas flaring in Nigeria. If the assumption that the more gas an organization flares, the more emission and pollution taxes it pays is correct, the first set of companies to hold responsible for air pollution and environmental degradation in Nigeria would, of course, be Shell Petroleum Development Company and Chevron Nigeria Limited. These companies paid the highest taxes ($44,787,000 and $44,570,000) in 15 years. Addax Petroleum Development Nigeria Ltd (ADDAX/APDNL), Nigerian Agip Oil Company (NAOC), and Mobil Producing Nigeria Limited (MPNU) follow. How much volume of gas have these top emission and pollution taxpayers flared in 15 years? Let’s dig into data. A little arithmetic might also be needed.

Charts E-I shows the top emission taxpayers, the amount paid in dollars and the exchange rates applicable in years covered by the data. Chart J shows the naira equivalent of the sum total of each company’s payments in those years. From the charts, it can be seen that Chevron appears to pay a little higher than Shell in naira while the converse is the case in dollars. It might therefore seem that one of these companies flares the most gas in Nigeria. However, a little more insight is required to draw any useful conclusions.

In Nigeria, there are regulations governing gas flaring. Over time, there have been different penalty rates per 1,000 Standard Cubic Foot (SCF). For example, N10 per 1,000SCF was applicable in 1998-2008 while, today, every 1,000SCF gas flared has attracted $3.5 (although, a report by NEITI states that, up until now, the penalty hasn’t been enforced and adhered to). Going by the former rate (N10 per 1,000SCF gas flared, which is still being paid by companies), Shell Petroleum Development Company paid N5,203,922,664 between 1999-2014. At N10 per 1,000SCF rate, the company had flared a total of 520,392,266,400 SCF gas (N5,203,922,664 divided by N10 and multiplied by 1,000). Using the same calculation model, Chevron Nigeria Limited flared 550,007,562,600 SCF gas, Addax Petroleum Development Nigeria Ltd flared 317,890,191,000 SCF gas, Nigerian Agip Oil Company 261,554,792,800 SCF and Mobil Producing Nigeria Limited flared 249,794,641,300 SCF gas.

Enlarge

OPEN DATA RESEARCH CENTRE, SMC

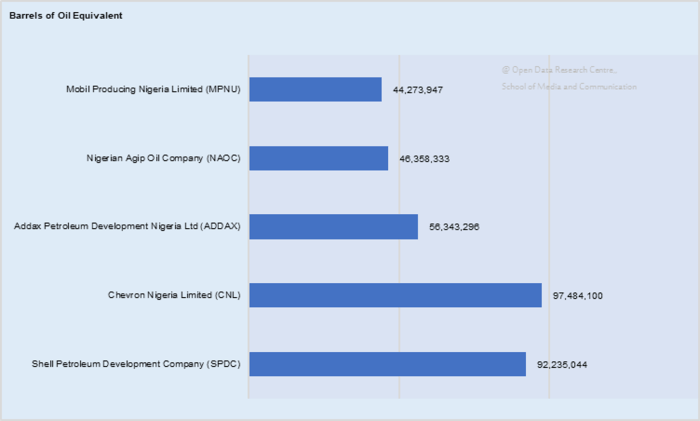

For those not familiar with SCF, the oil equivalent of the volume of gas flared might be easier to follow: If gas were to be oil, it simply means the five top companies had spilled more than 92 million, 97 million, 56 million, 46 million, and 44 million barrels of oil from 1999 – 2014 respectively. The chart below presents a clearer picture of this data.

Making Amends

The facts have not gone unnoticed. In 2015, the NNPC and Chevron Nigeria Limited (NNPC/CNL) Joint Venture revealed its plan to reduce gas flaring by 98 percent and it announced the completion and load-out of the topside module of the SONAM Non-Associated Gas, NAG, Wellhead Platform project in 2016. Unfortunately, the positive effect of this has not really been felt nor seen.

It was also reported that the Federal Government’s plan to end gas flaring is in the pipeline (pun unintended). The government also planned to introduce the “National Gas Flaring Commercialisation Programme”, an initiative that would generate about 36,000 direct jobs, 200,000 indirect jobs in the Niger Delta and ensure the redirection of the utility of gas for cooking, electricity and other industrial purposes.

In the meantime, Nigerians continue to suffer from the health hazards of gas flaring. The ordeal and agony of residents of Edo, Delta, Bayelsa, Imo, Akwa Ibom and Rivers states, (especially the host and neighboring communities of the oil and gas companies) are better imagined. Media reports have it that satellite images provided by the tracker located 222 of gas flaring incidents happening around 65 onshore oil wells these states.

Respiratory problems, cardiac diseases, bronchitis (inflammation of the lungs), silicosis (lung disease contracted by inhaling impure air) skin rashes, insomnia (sleeplessness), and eye irritations are some of the frequent ailments in such communities. The residents are exposed to all kinds of airborne diseases. Egbema and Mgbede and many more cases were reported in the media.

Should oil and gas companies continue to flare gas because they pay a fine of N10 per 1,000SCF (old penalty) or $3.5 per 1,000 SCF (new, but not enforced) for gas flaring? Certainly not. The companies are probably still flaring gas because they are able to escape the $3.5 penalty imposed on them by the government. This penalty is aimed at discouraging gas flaring, to encourage the redirection of gas flared from waste to wealth and preserve the environment and the lives of the residents in such environments.

The operators, rather than market or re-invent gas opt for flaring gas for obvious reasons (cheap alternative @N10 per 1000SCF). But, if the government enforces the new penalty, and calls back the debt of the organisations who paid at the rate of N10 rather than $3.5 (which is approximately N1000, at the rate of N360 to a dollar at the time of writing this article) per 1,000 SCF gas flared since 2008, it could go a long way to curb gas flaring. The organisations involved might have to pay heavily and as such, gas flaring would not be considered an alternative anymore.

The government seems to have made a move that could lead to this. Just a few weeks ago, on the 19th October, 2017, the House of Representatives passed a motion to set up an ad-hoc committee to investigate the non-payment of penalties on gas flaring by oil companies, post impact assessment of the affected environment, the payment of compensation to the affected communities as stated in the Community Development Agreement (CDA), and report back in eight weeks for further legislative action. This could be a step in the right direction. it could possibly generate a positive result for the greater good for the citizens, especially, oil and gas host communities. Fingers are still crossed.